Tasmanian tigers could be brought back from extinction if a multi-million dollar international science project is successful.

Create a free account to read this article

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

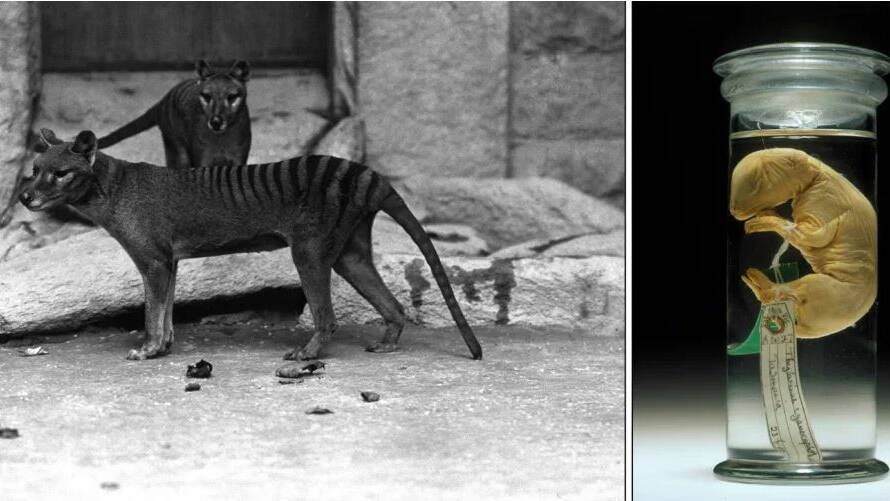

Australia's only marsupial apex predator died out in the 1930s, but scientists hope that the animal could be reintroduced into its native Tasmania within 10 years.

The project is an initiative of The University of Melbourne and Texas-based 'de-extinction' company Colossal. Last year Colossal announced it was planning to use genetic engineering techniques to recreate the woolly mammoth.

Earlier this year The University of Melbourne received a $5 million philanthropic gift to establish a research lab for de-extinction and marsupial conservation science.

We can develop the technologies to potentially bring back a species from extinction.

- The University of Melbourne's Professor Andrew Pask

The lab will be led by Professor Andrew Pask, who will develop technologies that could achieve de-extinction of the thylacine (commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger), and provide crucial tools for threatened species conservation.

"We can develop the technologies to potentially bring back a species from extinction and help safeguard other marsupials on the brink of disappearing," Professor Pask, from the School of BioSciences at the University of Melbourne said.

IN OTHER NEWS

Scientists will take stem cells from the fat-tailed dunnart, a living species with similar DNA, and then use genome editing to reconstruct the thylacine genome in marsupial stem cells.

"A high-quality genome is essential for thylacine de-extinction. This is because no live thylacine cell lines exist, so we cannot simply clone a thylacine - like Dolly the sheep," Prof Pask explains.

The cells will then be used to make an embryo which could be transferred into an artificial womb or dunnart surrogate.

What happened to the Tasmanian tigers?

The thylacine, a unique marsupial carnivore also known as the Tasmanian wolf, was once widespread in Australia, but was confined to the island of Tasmania by the time Europeans arrived in the 18th century.

It was soon hunted to extinction by colonists, with the last known animal dying in captivity in 1936.

"Of all the species proposed for de-extinction, the thylacine has arguably the most compelling case," Professor Pask said.

"The Tasmanian habitat has remained largely unchanged, providing the perfect environment to re-introduce the thylacine, and it is very likely its reintroduction would be beneficial for the whole ecosystem."

At least 39 Australian mammal species have gone extinct in the past 200 years, and nine are currently listed as critically endangered and at high risk of extinction.

"The tools and methods that will be developed in the TIGRR Hub [Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research Lab] will have immediate conservation benefits for marsupials and provide a means to protect diversity and protect against the loss of species that are threatened or endangered," Professor Pask said.